air

Zuri Camille de Souza

“Food is a reflection of the things we value and in that sense can teach us about our desires for ourselves, for others, for the world.”

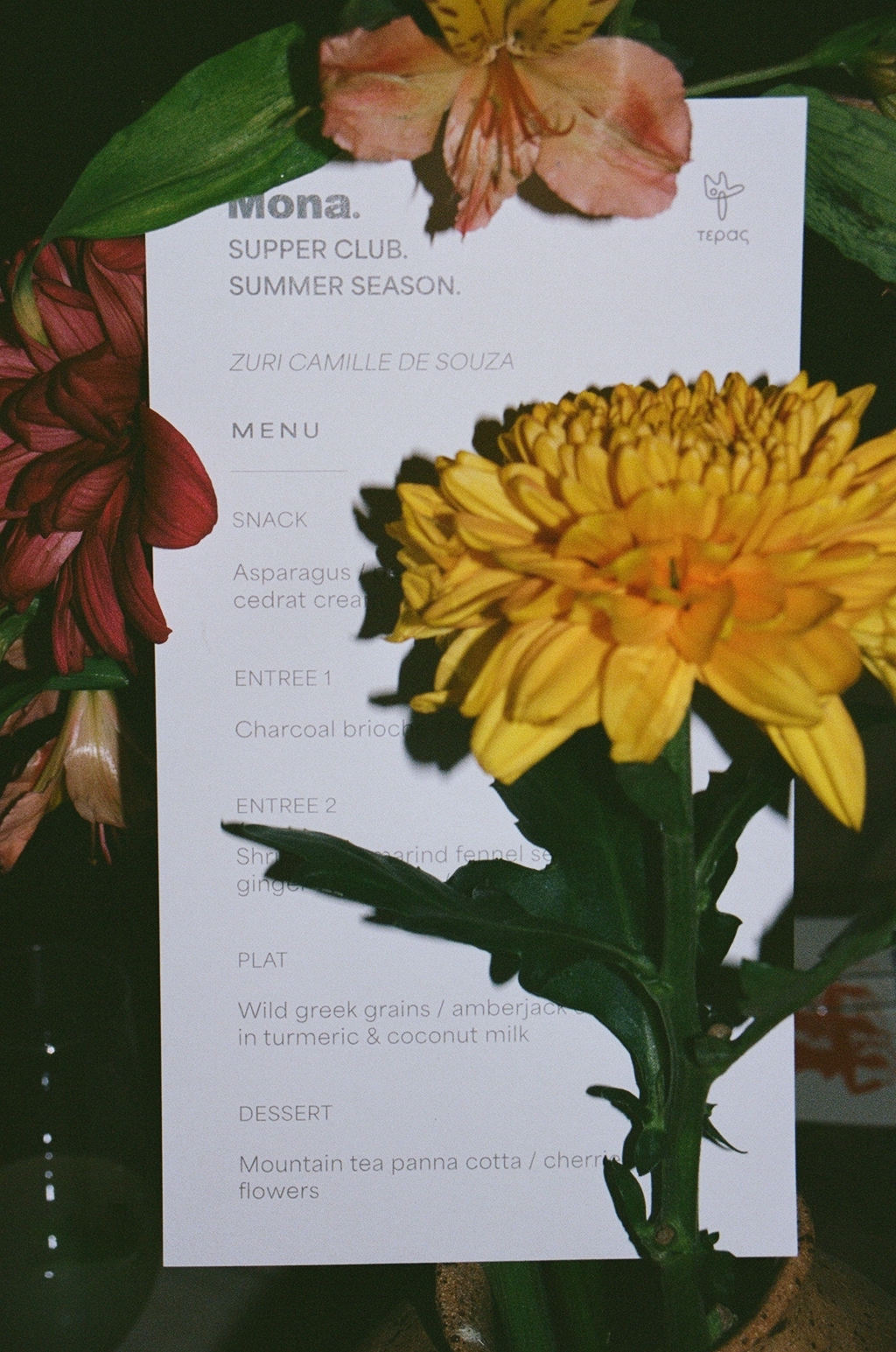

Based between Marseille and Goa, Zuri Camille de Souza is a cook whose eclectic childhood and array of influences show up on her plates like no other. This summer Zuri took over Mona’s Living Room as part of our Supper Club Series, where she merged the coastal Indian food she grew up eating, with local produce sourced in Athens. We spoke to her about her unique approach to cooking as a practice, awareness of mental health within the setting of a kitchen, and where she continues to draw inspiration from.

HOUSE OF SHILA (HOS): Your cooking practice is very inspired by your childhood and your parents in South India. Could you tell us a bit about how you were raised shaped your approach towards ingredients, cooking, dishes, and eating?

ZURI CAMILLE DE SOUZA (ZS): Although both my parents come from South India, their cultural and religious backgrounds aren’t the same. My father was born into a catholic family from Goa but living in Nairobi; my mother into a hindu family from Bombay and Pune but grew up between Trinidad, Hong Kong, Mauritius and Zambia. My parents both came back to India for college, during a time when India was growing herself as a country. They both grew up in a time of cultural questioning, critical thinking and socialism, and their own story is complex in the context of India; although diverse as a country, intercommunal, inter-religious interactions are very regulated by social customs and not necessarily welcome. I often thank my grandparents for how open they were. It might seem strange in the Global North to imagine marriages or love stories as matters of an entire family but at home, they most definitely are, even today.

This cultural métissage is something that my brother Zaeen and I both grew up with. We celebrated Hindu and Christian festivals, ate food that came from two communities, Goan and Maharashtrian; learnt our maternal and paternal languages and forgot them only to learn other languages; felt equally out of place and familiar wherever we went.

At home, so much is communicated through what we eat, it is such a powerful part of people’s identity. We were fascinated by the travelling our parents had done, the places they had seen; food was an intrinsic part of these stories we listened to—my grandmother Dora roasting Kenyan coffee each morning when they lived in Mombasa; the frozen Mars bars that my mother would buy after school in Hong Kong; the Dutch neighbour’s daughter who would sneak into my Aji’s kitchen to eat freshly made rotis with them; the picnics in Zambia.

Along with these narratives, my parents also spoke of the landscapes they encountered–the hills and forests and beaches, the oceans they sailed across to come back to India, the gardens they tended to. From our house in a village in Goa where I was born to the small city houses, my father always found space to make a garden. Nature was something to value and care for, we were taught this from a young age.

My approach to food is born out of all these childhood experiences, I think!

HOS: How do you experience the way that food can teach us about ourselves, our identities, perhaps even our desires?

ZS: I think food is a reflection of the things we value and in that sense can teach us about our desires for ourselves, for others, for the world. It can be a little glance into our dreams–when we cook with honesty and truth. Of course, it can be conceptual and complex and an exercise in technical skill, it can be a dreary task one might do to earn a living, it might be done with the kindest intention yet the simplest products. It could just be a pure expression of ego. I’m currently reading three interviews by John Coltrane (Je pars d’un point et je vais le plus loin possible : Entretiens suivis d’une lettre à Don DeMichael) and it is helping me understand my creative process as a chef and how I would like to engage with my cultural identity through my food.

HOS: Your practice often circles around words such as joy, pleasure, and ritual, what is the role of such positive emotions and the heartfelt methodologies that might conjure them?

ZS: When I started cooking–not too long ago, in 2019–I just felt such a separation between the emotions I value and the ways people often cook in the kitchen. Although cooking is a hard, back-breaking job (quite literally), I just started to ask myself at some point why I had to subscribe to those emotions to get better. I do believe in discipline and rigour and hard work, I don’t think there are shortcuts to doing something well but I prefer to imagine cooking as dancing or playing music in an ensemble rather than imagining it as a military composition as it is often portrayed.

In both the dance and music I enjoy, there is such a fine balance between freedom and communal understanding. There is joy, there is pleasure, there is dedication. There is a harmony between ideas and the body, there is hard work, there is practice. And I believe that when all of these things come together, there is something deeply spiritual and ritualistic about my work.

HOS: Your IG handle sensualecology is the first time I’ve seen those two words juxtaposed. They feel so luscious. It also seems you might have coined the term (?). What does sensual ecology mean?

ZS: Sensual ecology is something I thought of whilst working in Dubai. Sounds strange, I know. I actually wanted to study urban design and got into Parsons The New School in NYC. However, I needed to work in order to finance my studies and so after deferring for a year, I found a job doing graphic design in Dubai through a friend. It was such an absolute shock for me to find such a separation between what is constructed and what is natural and I began finding such delight in discovering little plants and natural spaces that subverted the rigid urban planning and construction. I found a certain poetry in the way things managed to grow in such unforgiving climates, in the simple expressions of wildness that I came across through the city–bougainvillaea flowers on a sandy pavement that hadn’t yet been swept up and cleaned, milkweed shrubs growing through scaffolding on abandoned construction sites, acacia with budding leaves. It reminded me that the desert below us was once an ecosystem with its own intricate balance. I eventually lost my job and didn’t make it to Parsons (don’t be sad, it worked out perfectly!) but I spent a month in Dubai before leaving trying to figure out what to do. I started interviewing friends about their memories of nature, exploring the emotional qualities of landscapes (I was also reading the Poetics of Space at the time, a book I still hold dear) and realised then how much of our perception of nature is sensual, tactile, emotional. I think I just want to bring attention to the sides of nature that are less technical and productive and more ethereal, immediate and intuitive.

“Food is inherently political—historically in India, the type of food one eats, the amount of food one eats, when one might eat; all these things are decided by caste, class and gender.”

HOS: You live in Marseille. What led you there and how would you describe this city to someone who’s never been?

ZS: I met Jimmy, my boyfriend, in Bombay. He is French. After a few years together in India, we left to work in Palestine and Lesvos for a year, doing a project bringing together books on access to nature, migration and community gardening through a publishing house we set up .

After a year, when the project was over and we passed on the garden to the next team, we couldn’t think of anywhere else that we would feel happy after Bombay except Marseille.

Growing up in India, Marseille feels very familiar to me. I feel at home with the heat, the smells, the extreme emotions. It is a small town and a big sprawling city. I find myself complaining about the Parisians too, scowling at the tourists in the summer that make the water smell like sun cream (I’m sure you’re dealing with that in Greece too); I am happy to discuss the mistral whilst sipping a pac à l’eau in the cafe. I love my morning swim in December when the beach is empty and the water freezing. I like Noailles as it is–diverse, loud, a hundred languages spoken on every corner; I feel sad when I see the small shops close, when Doudja, the Algerian lady who baked bread for all my events left (was the rent too expensive?), it bothers me when the people who live in the neighbourhoods are not put before those with money. I am uncomfortable when I hear prejudiced opinions of certain areas of the city.

It is hard to describe something so familiar but I can say that Marseille is complex. Marseille needs to be cared for, be gentle and kind and try to take less whilst visiting; it is, strangely enough, a safe space for many of the people who live there, even if there are such immense infrastructural problems.

HOS: For you, your cooking practice is not limited to the act of making food alone but also encompasses, ‘the art of hosting and nourishing, bringing together creativity and pleasure in food.’ It seems to put yourself as somebody very involved in the dynamic between cook and eater. How does this relation inspire you and the dishes? What could we consider as the ‘art of hosting and nourishing’?

I think the simplest way to describe this is the feeling I get when I would arrive to my grandmother’s house for the summer holidays before dawn, and she would be awake, smelling of jasmine and rose soap, fresh in a beautiful silk sari with a pot of darjeeling tea and biscuits ready to offer us something after the overnight journey. I think it is important to consider every single gesture, even to how we put the salt or a single flower petal on a dish.

HOS: Can food be political? You recently expressed how standing against any sort of oppression is a fundamental element of your work. Can you talk us through this notion and how you navigate the world in support of your personal values?

ZS: Food is inherently political—historically in India, the type of food one eats, the amount of food one eats, when one might eat; all these things are decided by caste, class and gender. A woman traditionally serves her husband and all the men in the family and then eats the leftovers. That is normal. A dalit cannot drink water from a certain well because they are considered impure. That is a social norm. A Muslim person is lynched for transporting beef. This is celebrated. In India, multicultural, pluri-religious food identities are being erased by a homogenised and upper-caste Hindu version; alongside, agricultural systems and traditional culinary heritages being replaced by industrialised farming that is detrimental to the land. I intentionally choose to cook food that subverts these norms, that speaks of the richness and poetry one can find at home.

But more globally, people are dying of famine as I write this and food systems are broken-–whether in Sudan, Palestine, Yemen, Haiti, Congo. Food is weaponized consistently in times of conflict—consider the Israeli blockade on aid into Gaza and the Israeli army’s consistent destruction of fertile land in Occupied Palestine. Consider agricultural reforms in Europe that prioritise pesticides over ecology and industries over small-scale economies or similar policies being implemented in India and the violent repression that followed their protests.

My work is often in spaces of privilege, and one can argue that cooking itself is a luxury, to choose what to eat, to be able to eat out, to have access to good produce. It is not always easy for me to navigate through this and many are the moments in which I question myself. I am not sure how most people do it! I try to balance these anxieties by staying humble, always. In the end, I am just a cook. It is a simple job and doesn’t need to get to my head!

I think an important part of staying humble is also about the way I run a kitchen and being respectful to every single person and their work–from the commis to the manager, but especially to people who traditionally have the hardest jobs, the cleaning staff and the dishwashers, without whom a kitchen cannot function.

“My work is often in spaces of privilege, and one can argue that cooking itself is a luxury, to choose what to eat, to be able to eat out, to have access to good produce.”

HOS: Could you tell us about the dishes you created for your residency at Mona. What was the concept, and did you just know what you wanted to create whilst in Athens? You have been keen to go to local markets and collect certain herbs.

The only thing I was sure about was the mountain tea, which I absolutely love. I am passionate about traditional herbal knowledges and adore the markets in Greece because all the aromatic plants here are such a treasure. I also remember the cherries from my time in Lesvos. Besides that I knew I wanted fresh seafood, to create a menu that brings together the coastal Indian food I grew up eating with produce found locally. I’ve actually been working on the menu since your invitation to cook during winter. I always do drafts of menus that evolve consistently until I feel it is coherent.

HOS: What really stands out is how you speak on the sensitivities towards mental health in your kitchen. I can think of another instance where I’ve seen a chef say they make a commitment to the mental health of their staff and kitchen. Where does this motivation come from, and how do you implement a kitchen with these sensibilities, what does that look like?

I was actually bullied a lot in my first job in Marseille and I couldn’t speak French well enough to respond. I remember crying every single evening for months–it was so unpleasant! I promised myself I would never be this person.

I also know that there is a particular expectation of people to adapt and integrate into a new place, whethera new kitchen, job or country. Whilst I will always respect a space that I have been welcomed into, I don’t believe in carrying on traditions that aren’t healthy. I think that the practices we put into place today can become traditions tomorrow—I can’t accept suffering, alienation and harassment as normal occurrences in work spaces. No kitchen can function if its team isn’t healthy and happy. If you pay attention the next time you go out, it’s easy to tell when someone sad is cooking.

On the other hand, I have also noticed that there is a huge expectation from straight men in my team that I am always soft, kind and forgiving and I don’t necessarily identify with the role of the mother in a kitchen. I do, however, believe that we can formulate a more feminine leadership that is more progressive and respectful than the systems currently in place (and I mean this both in and out of the kitchen!)

Practically, I try to communicate as clearly with my team as possible. I let them know my expectations and I define roles. I think in any creative process there is a framework that can give guidance as well as reassurance. I have been lucky to work under chefs who do run their teams like this and it deeply influenced me.

“I think an important part of staying humble is also about the way I run a kitchen and being respectful to every single person and their work.”

HOS: Could you share with us a memory of one of your most formative experiences? It can be about cooking, or not, just an instance that contributed to shaping you into who you are today?

ZS: I do think that question is harder to answer than asking me what my favourite dish might be!

But maybe, I think the first time I put my head under the water and saw actual things–it was in Lesvos, in 2018, and I remember being amazed by the fish and seagrass and the clarity of the water. I have been swimming since before I could walk by the Arabian sea on the West coast of India but it has sandy, cloudy water. Or maybe the first time I saw snow when I was 18.

HOS: Is there something that you draw inspiration from that people might be surprised by?

ZS Being underwater. I love free-diving and could spend all day in the sea. I don’t actually cook much fish but there is a world under the water that is so profoundly spiritual and beautiful to me.

HOS: If you had to say one person that you love cooking for the most, who would it be? And who would be your dream dinner date?

ZS: I think Miles Davis, in his fruit diet phase. Or maybe, Sade?

HOS: Is there a flavour, a taste, or an ingredient that you only had once and are ever on the hunt for?

ZS: I have a vague childhood memory of drinking rose sherbet sitting on a white sunlit patio in Goa. I am not sure where and my mother doesn’t know either, light filtering in through gauze curtains. It was so cooling and floral without being too sweet. Maybe that flavour.

HOS: Could you tell us about a recent meal you really enjoyed. Set the scene…

ZS: Sitting in an orange orchard in the Villa Medicis in Rome (I was chef in residence there for a year) sharing a plate of pasta with fresh peas, in the sun with my mother. The orange trees were in bloom, the air, replete with their perfume. It was spring, warm sunlight and fresh breeze. I just remember seeing my mother so happy and felt such gratitude to be able to share that moment with her.

HOS: Lastly, do you hold any special food memories from Athens or Greece? If Athens was a dish what would it be?

ZS: Definitely a meal I shared with Jimmy on the island of Fournoi. It was late October and after the tourist season. We were sailing back from Lesvos and stopping at islands along the way. I remember we were unable to row to the shore because of the wind blowing down from the hills so we swam to the beach and found a little (the only) taverna open. I remember eating the most delicious fish that the owner caught that morning. These moments are worth so much to me.