HOS: Where else do you draw inspiration from?

MR: First it was films: female characters in old films. I was transfixed and bewildered by their being and it felt like a puzzle I needed to solve. Then after that, I would get ideas from my life. I don’t know why it took so long to realize that my life and identity had been moulded by these women. I had modelled since I was very young for many years. Of course I was constantly confronted with these ideas!

HOS: Tell us about building your house in the woods.

MR: I think it goes back to the utopic idea of having somewhere to go to build your own world. I wanted to create everything and then be the character in that. I had a weekend house for several years where I got to try this out. Later on I found another place, a large construction that used to be some sort of yesteryear club for gentlemen. It was big enough where I could use it as my studio: I have a printing room, a room for photoshoots, a wig and costume room, an art storage room, a mannequin storage and space for living as well.

It’s on top of a hill but there are still trees on all sides, you have a vantage to see out while feeling protected by the forest. It’s a very plain house. Nothing special on the outside. When you walk through the door it’s a surprise, like going into another dimension. I kept the original look of the place, the midcentury club vibe and then tiled everything else that needed help in black and white.

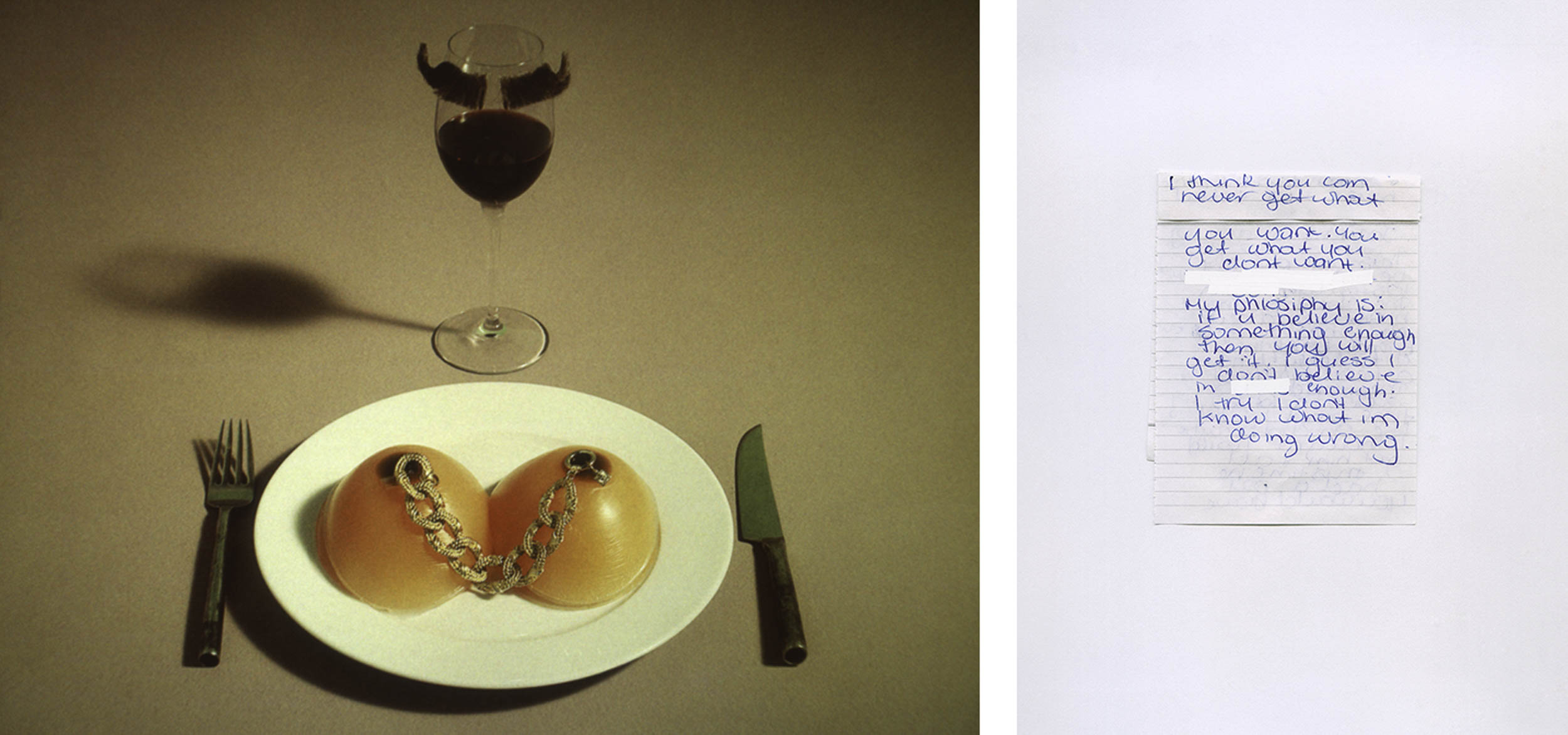

HOS: You transitioned from modelling to being an artist, with many references in your work evolving around the idea of beauty. How do you approach the obsession with beauty/objectification of women?

MR: Because I grew up in a business revolving around beauty it took me a long time to be able to see outside of it. All of my friends were models and the industry felt like a big family. As long as you worked on being their version of beauty you were accepted. This started to crumble as I got older; by older I mean being in your twenties. At 30 it was the end. And the moment I stopped I felt better than I had ever felt, but you don’t know that. All along the way you are oblivious. I like to use what I’ve known and present it as a parody. I still want to fit the parameters, use part of the language with this beauty, but then tell a different story. I’m not dictating too much of this and that, I want the viewer to have a realisation for themselves.

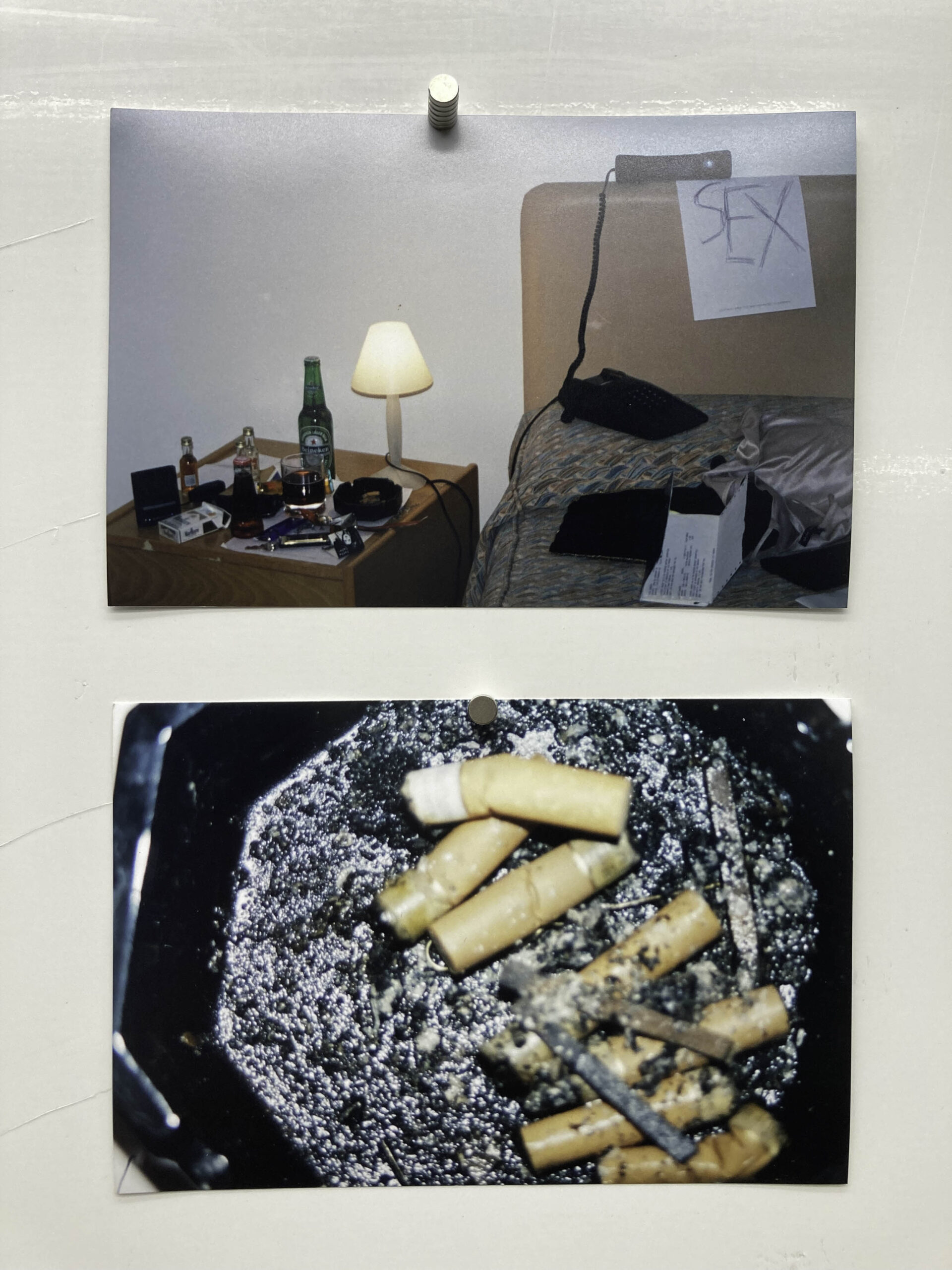

HOS: There is a play in your work in blurring the boundaries between fiction and reality, and often you are your protagonist filming it all solo. How do you navigate between those worlds?

MR: Like I hinted earlier, photography allows you to merge these two worlds perfectly. You only see what’s in frame while trying to imagine what’s out of frame. A photograph used to be a blueprint of what is real: you knew what you saw could not be altered. And even though you can alter anything now, it’s still understood that a photo is meant to be real. But maybe now it’s like painting with real life. The mannequins are perfect to navigate this in between space. They are a representation and are made of plastic, and I am a human that is so made up I look like a doll. So together we come closer to meeting at the line. And in this the mannequin becomes humanised and I become otherworldly.